The Reading Matrix

Vol. 2, No. 2, June 2002

Web literacy, web literacies or just literacies on the web?

Reflections from a study of personal homepages

Anna-Malin Karlsson Abstract

This article raises the question of whether or not we can talk about such a thing as web literacy in general. Perspectives from media studies, literacy studies and the study of multimodal texts are used to find the main contextual parameters involved in what we might want to call web literacy. The parameters suggested are material conditions, domain, power or ideology and semiotic mode. These four factors, and their relevance for describing literacy on the web, are then further discussed by experiences from an empirical study of personal homepages. The results from this study are accounted for in terms of the literacy practices connected to the pages, the conceptions of textual norms among the users and in terms of the textual role played by writing in relation to other textual elements. In all these three aspects the personal homepage is highly heterogeneous. You find what might be call modern conceptions of texts as multimodal units, as well as more traditional writing. It is argued that web literacy should be understood as literacies, and furthermore as socially situated practices rather than technologically determined conventions of reading and writing. Thus, the parameter of domain (public-private, local-global, professional-"vernacular") is of great importance.

Introduction There are numerous examples of how new technologies and new media have been subject to intense discussion focusing on their supposed impact on social life and on language use. Sometimes the new media in question have been demonized and said to have a largely negative effect on human conditions, as was the case with television and even more so with the video recorder. The Internet has instead been largely idealized. We often hear of its almost revolutionary power to give voice to everyone, irrespective of a person's political or financial position. Also highlighted is its technical potential as a means of creating a completely new kind of text structure. It is true that the public arena has been greatly expanded through the Internet and that the traditional roles of speaker and listener, writer and reader, have become to some extent diffuse. These changes, together with the text-creating potentials of the new medium, have made it possible for certain new text products to emerge. But that is not to say that web literacy is something unitary and in all aspects different from traditional literacy or literacies. At this point, there are too few studies of different web uses and web texts for us to be able to say anything in general. This paper will hopefully help to increase knowledge about web-related reading and writing, and contribute to the discussion of the relation between the medium and the message. I will mainly draw on an investigation of personal homepages from an informal Swedish web community from 1998 (Karlsson, 2002a). First, however, I will discuss some relevant theoretical frameworks for dealing with media and literacy. Perspectives from media and communication studies, literacy research, and studies of multimodality will be used. I will then present the homepage study as an empirical base for further discussion. Background The medium and the message Among media researchers, technology is a natural focus, and one perpetually ongoing discussion deals with the relation between the medium and the content - or between the medium and the message. Radio and television have both generated intense debate on the question of the effects of technology, and both media were widely considered to be tremendously different from all preceding media - so revolutionizing that the use of them would change human communication for good. Williams (1974) reflects on the debate about television and formulates nine statements about television technology which extend from technical determinism on one side to a more dynamic view of technology as a symptom of social changes on the other. The most deterministic statement reads as follows: (i) Television was invented as a result of scientific and technical research. Its power as a medium of news and entertainment was then so great that it altered all preceding media of news and entertainment. (Williams, 1974, p.11)

Thus, scientific and technical research is understood to be an autonomous activity, motivated more or less automatically by its own internal goals. When television was created, it was shown to be the most superior way of relaying news and entertainment. In Williams' statement reflecting the opposite end of the spectrum, technological achievements are still understood to be automatic and autonomous, but here their impact on society is problematized: the needs of society and certain aspects of the potential of television intersect and develop in symbiosis. (ix) Television became available as a result of scientific and technical research, and in its character and uses both served and exploited the needs of a new kind of large-scale and complex but atomised society. (Williams, 1974, p. 12)

According to Williams, a significant feature of the determinist view is the idea that technology is developed by incident, i.e. with no specific aim and for no specific reason. Thus, the impacts on society are also incidental, since they are caused by technology alone and not by any underlying historical forces. As we can see, the second, diametrically opposed statement also includes an understanding of technological development as being without specific aims or reasons. The difference is the focus on how it is made use of. Here, the needs of human society are the determining factor, and technology has no significant meaning outside this use, which in its turn is caused by social conditions. This means that if television had not been invented, the needs of human society that developed as a result of social and historical conditions would have been fulfilled by some other technology. In Williams' opinion, both these positions fail when they separate technology from society, in viewing technology as a self-generating process. Instead, Williams suggests an alternate understanding where the development of technology (i.e. television) is driven intentionally by social and cultural needs. At the same time, the social and cultural conditions are shaped in part by technological development; they can not be separated from one another. Researchers with a special interest in Internet language use tend to consider the medium, networks of computers, as the main contextual feature and the most important reason why the language and texts on the net look the way they do. One of the earliest volumes on Internet language and Internet communication, Computer mediated communication (Herring, 1996), reflects the extensive interest in the linguistic structure of Internet interaction. Many contributions compare computer-mediated language to typical spoken and written language, arguing that computer-mediated language is to be found somewhere in-between. One essay describes "electronic language" as "a new variety of English" (Collot & Belmore, 1996). A common feature in these works is the focus on language on the level of system, or variety, not text or genre. The discussion also typically departs from investigations of online synchronous or slightly delayed communication such as chat or e-mail. These are most likely the instances of Internet communication where the medium makes the most difference, compared to everyday face-to-face oral conversation. In addition, more typically monological texts can be studied, and a strong focus can be placed on the medium, as in hypertext research, where most researchers have their roots in literary studies. The way information is stored digitally, made possible by computer technology, is built into a theory of narrative (i.e. Landow, 1992; Aarseth, 1997; 1999). In general, hypertext here refers to the hierarchical or network-like structures in which readers can choose their own textual sequence by clicking on some links rather than others. Despite the interest in the reader's path through the text, hypertext theory is strongly occupied with the author and his or her conscious exploitation of the unique properties of the medium. Thus, the main interest of hypertext research, like the focus of the concept itself, seems to be the originality of the unique work, and not so much everyday Internet reading (and writing) practice or the reading practice of ordinary readers. Interestingly enough, when the role of the reader is addressed explicitly (e.g. Svedjedal, 2000) somewhat different conceptions of hypertext are produced. As readers often have the possibility of reading texts in a non-linear way, academic papers with footnotes could also qualify as hypertexts from this perspective. Thus, the technology of storing text might not be all that determinative in how the text is used after all. Different conceptions of literacy The term 'web literacy' combines the focus on the medium with a concept, which is far from unambiguous in research and education history. The traditional conception of literacy makes it a rather cognitive phenomenon. In literacy research, reading and writing skills were long seen as being connected to logic and abstract thinking, while illiteracy (in individuals as well as in societies) was assumed to be connected to less advanced mental skills. Researchers in this tradition (cf. Ong, 1982) tended to treat literacy as one single, autonomous thing, stressing that the most important feature of the phenomenon was that it differed from spoken communication at all levels, and in all instances. If literacy is conceived as something ideal, as a competence to achieve, it is not surprising that the majority of literacy studies take a pedagogical perspective. The term adult literacy, in English-speaking societies, refers to different kinds of programs aimed at remedying reading and writing difficulties and even illiteracy among the less educated parts of the population. A great deal of the research on literacy is also conducted in educational settings, where the writing development of students is followed and the structure of different academic genres is described and explained (e.g. Swales, 1990). Likewise in the field of professional writing, the pedagogical aim is obvious, and the areas studied are mainly law and business - target areas of important academic education programs. Here too different genres are described and structural patterns are uncovered (e.g. Bhatia, 1993). During the last few decades, the so-called New Literacy studies have raised questions about the social constructions of literacy (Street, 1984; Barton, 1994; Gee, 1996). From their perspective, literacy can never be understood as objective and ideologically neutral. Every use of writing is shaped in and by its social context, which means that even the most established and institutionalized conceptions of literacy can be traced back to social and cultural conventions and needs, as can any conception of prototypes. Each attempt to define literacy must both depart from and include the social institutions that surround and support it. Street (1984, p. 1) defines literacy as "the social practices and conceptions of reading and writing" (Street, 1984, p.1). Consequently, he talks about literacies, in the plural, instead of literacy. Gee (1996) also prefers literacies to literacy. In Gee's view, more important than the difference between speaking and writing as such is the difference between what he calls primary and secondary discourses (p. 122). A typical primary discourse is the spoken, private language acquired by children in their homes. School language, spoken as well as written, is the first secondary discourse that children encounter. According to Gee, writing is not really a necessary component for defining what we traditionally mean by literacy. What is more important is the fact that it refers to language conventions in a particular domain. Instead he suggests that we talk about "mastery of community-based or more public-sphere secondary discourses" (p. 144). In western culture this kind of discourse is almost always written, but in other cultures it might very well be spoken. As Gee argues, this shows that use and cultural function are more interesting than technology. An important area of interest in New Literacy studies is what has been called vernacular literacy, or everyday reading and writing (e.g Barton & Hamilton, 1998). There is, however, a third aspect to the concept of literacy in which its seemingly obvious connection to letters and written words is problematized. Among linguists and discourse analysts, the book Reading Images (1996) by Kress & van Leeuwen has had great influence. It is claimed in this work that all texts are multimodal, i.e. all texts are built up by more than one semiotic mode. Spoken texts consist of language, but also of sound and sometimes movements and gestures. Written texts also include layout, color, type fonts and images. According to Kress & van Leeuwen, there is reason to talk about a new visual literacy, emerging with the use of new media. This new visual literacy involves the understanding of how visual, non-linguistic modes create meaning together with language, as in TV commercials or in tabloid newspapers, for instance. However, as always, education institutions cherish more monomodal texts, such as the literary novel and the academic paper, which are traditionally highly valued. Thus, according to Kress & van Leeuwen, schools today risk educating a generation who are illiterate when they enter the new, multimodal media landscape. In their most recent book on the subject, Kress & van Leeuwen (2001) further develop what is new in the new visual literacy. They find that it is not only the fact that texts tend to be more multimodal than before. The different modalities also seem to be less specialized: In the past, and in many contexts still today, multimodal texts (such as films or newspapers) were organised as hierarchies of specialist modes integrated by an editing process. Moreover, they were produced this way, with different hierarchically organised specialists in charge of the different modes, and an editing process bringing their work together.

Today, however, in the age of digitisation, the different modes have technically become the same at some level of representation, and they can be operated by one multi-skilled person, using one interface, one mode of physical manipulation, so that he or she can ask at every point: 'Shall I express this with sound or music?' 'Shall I say this visually or verbally?', and so on. (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2001, p. 2)

Summing up the parameters involved If we now consider the different perspectives on web literacy suggested above, we can see that there are a number of parameters involved. First we have the material conditions and the technology used to shape the material. Traditional literacy makes use of paper and ink or some other kind of coloring material. The technologies used to inscribe text have either been handwriting or printing, both rendering a flat paper surface of a standardized size with visible marks ordered in regular lines. When one page is full, the text normally continues on the next page. Texts on the web are made out of different material. Visible marks are made to appear on a screen using a keyboard. They are not inscribed on a flat surface of paper but stored digitally. Thus, the storing and the display of web text are two different things. Although made up of digital data, without surface or traditional linearity, web texts may be displayed in ways that are fairly similar to black print on white paper. They can also be displayed in very different ways, as blinking green rows of text descending from the top of the screen against a wavy pink and purple background. The material conditions of web texts can be used either to make the text fit into traditional patterns or to make it as non-prototypical as possible. The material - and the technology connected to it - does not force a specific form onto the texts. Nor can it be said to force a specific kind of literacy onto its users. It provides means to do things in very much the traditional way, but it also provides the opportunity to do things very differently. Another parameter is the one of domain. Literacy can be public or private, global or local. It can also be either professional or tied to everyday life. Web literacy takes place in a medium that has the power to make it public and global. Therefore we tend to think about it that way. However it is not certain that the use of Internet text can always be describe in such terms. Once again, the technological potential can easily be confused with actual use. My experience is in fact that quite a lot of reading and writing on the web is rather private and local. It might be less controversial to state that a considerable share of Internet texts are written and used in non-professional settings. Closely related to the domain is a parameter that we might call power relations or ideology. Traditionally, a number of institutions such as school, publishers and the press have determined what kind of writing is correct or good or should be published and seen. Often there has been some kind of consensus between these institutions, and words such as writing and writer can not be defined without adding certain values and ideological constructions. The Internet, and especially the web, provides space for anyone who wants to publish something. Even though institutions similar to publishing houses and newspaper editors are beginning to appear on the net, the web has long been an arena where the traditional roles and power relations of the media market are dispersed. You might suppose that this would also happen to the ideological construction of what writing is and who constitutes a writer. However the powerful institutions mentioned above are still in place, and ideological change is probably a rather slow process. Finally, there is the parameter of semiotic mode. The web here falls under the development sketched out by Kress & van Leeuwen (2001), where a wider variety of material resources and thus semiotic modes are available for the text-maker. An increased (public) use of different modes for different purposes might of course, as suggested by Kress & van Leeuwen, lead to less specialization between different semiotic modes. This might in turn mean that language for example could lose its dominant position as the main semiotic mode in most texts of importance in society. At least you would expect web text to be more multimodal than the prototypical paper text, as the web medium encourages text making with more and other means than verbal language to a larger extent. Thus, web literacy in general might be described in terms of changes in at least four contextual parameters: the web has brought a new technology to text making which enables different text structures than traditionally; it has blurred the borders between public and private (or rather, it makes all texts globally available, whether intended or not); it changes the traditional roles of readers and writers and challenges the dominant view of what writing is, and it has put new systems of meaning-making into the hands of homepage owners. None of these changes alone can be assumed to be a determining factor more than the other, it can not be anticipated how the changes will co-vary and shape a specific web literacy - or several different literacies. In the following section, I will report on one empirical study that hopefully can shed some light on one part of the web and the possible literacies tied to it, that is, the world of personal homepages. Empirical ground for the discussion: a study of personal homepages The purpose of the investigation (Karlsson, 2002a) was both to explore the personal homepage and its use in a more general sense and to characterize it as a product of writing. It was assumed that a text is best understood as a part of a text culture in a wider sense, and that any product of writing can be placed in its literacy tradition. More specifically, the question was raised as to whether the personal homepage should be seen as a part of a tradition of private, non-public writing or as a lay contribution to the otherwise professionally-governed mass media market. The main material consisted of 26 personal homepages assembled in 1998. It can be described as a loose network of pages, connected to each other through links on what are called friends pages and in guestbooks. The owners of these homepages took part in the investigation as informants, together with 17 writers of net diaries found through a diary community administered by one of the homepage owners. The diaries of these so-called reloaders, as well as other web pages made by the informants, are used as additional source material for obtaining knowledge about homepage use. For experiments and interviews, I also used a number of pages created by other people found in the networks linked with the main group of informants. A variety of methods were used in the study. The focus here is on the methods involving informants: interviews, experiments and to some extent on-line observations. Questionnaires were used, as well as individual interviews. An important part of the work with the informants was carried out as experiments. Their main purpose were to determine the textual norms (e.g. Berge, 1993) of the informants, both the norms concerning what counts as a homepage text Berge, 1993) of the informants, both the norms concerning what counts as a homepage text and the norms establishing what a good homepage text is. The results will be summarized below according to three themes: first in terms of literacy practices, second in terms of norm conceptions among the informants, and third in terms of the role of writing in homepage texts. Literacy practices To study literacy in terms of literacy practices (Barton, 1994) - and, in more detail, in literacy events (Heath, 1983) - is a way of contextualizing and situating literacy that is widely used in New Literacy studies. Literacy is then seen as mainly a social practice, and the extent to which writing plays an important role in the practice is an open question. The interview data were analyzed to give a picture of what the informants do with homepages. Expressions of activity, such as "copy and modify codes", "join web rings" and "add something new" were excerpted from the data and sorted according to different themes. A number of possible literacy practices could be distinguished as a result: - looking for inspiration and making plans

- learning and teaching

- producing

- judging and being judged

- promoting the page

- administering and maintaining (both as a producer and as a consumer)

- changing and renewing

- stating your opinion

- publishing yourself

- socializing with friends

- demonstrating friendship

- surfing (visiting other pages without a specific plan) Of these, not all can be said to be literacy practices to the same extent. When the role of writing is considered, it can be concluded that writing is dominant in practices promoting the page as well as in judging and being judged, socializing with friends and demonstrating friendship. When they talked about these practices, the informants mentioned "writing" as an explicit activity. Practices concerning the production of the page, including planning and learning, are more genuinely multimodal, as is the practice of surfing. In this respect, the informants rather talk about "making" or "using", and it is more difficult to separate writing and reading from the activities carried out. Conceptions of norms When the informants were asked to reconstruct a typology of pages, seven categories were formed: the pre-page, the index page, the ego page, the link page, the friends page, the photo page, and the content page, which is a miscellaneous category. To these I added the diary, which was already named by the informants in the interviews. In the experiments used to reconstruct the textual norms of this specific community, the eight page categories in all functioned as an important base, which means that their relevance was tested further. It was then obvious that different categories could be tied to different kind of norms. Moreover, the norms seemed to be connected to writing to a different extent and in different ways according to the page category. (See also Karlsson, 2002b.) Good pre-pages were described as legible, tempting and easy to use. The most important visual element on the pre-page is that connected to the link to continue. This element can be of almost any type, as long as it is placed in the center of the page and attracts the attention of the visitor. According to the informants, the index page should also be legible and easy to navigate from. But it should also contain "text", that is, writing. The most frequent visual elements in the index pages in my material were lines of writing followed by blocks of writing. Four out of five index pages contain a list. Describing the ego pages, the informants talked more specifically about writing and distinguished between two main visual forms: running text and lists, although these were labeled somewhat differently by different informants. Even though they agreed that these were the two main ways of organizing the content on an ego page, they disagreed on what is preferable. There was, however, a common view on what style is connected to the different visual forms: running text suggests a personal tone whereas lists mean that the ego page is impersonal and based on facts. When the ego pages in the material were studied, it was seen that the distribution of different types of elements on the ego pages was similar to that of the index pages, i.e. elements of writing dominate. Link pages and friends pages could be assumed to be similar to each other, but the informants' descriptions differed, especially in how they are valued. Link pages should preferably be well organized and concise, while friends pages should be personal and contain running text, i.e. longer and more elaborate presentations of each friend. The link pages consist mainly of well separated lines of writing and what might be called abstract visualizations (non-representative visual forms) used as organizing devices. On the friends pages we instead find groupings of lines of writing, photographs or visual representations and blocks of writing, with each group representing a friend (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Groups of elements on a friends page The photo pages were in many ways treated in the same way as the friends pages. The informants value what they call "information", a feature which in this case is expected to be expressed in writing. Furthermore, the distribution of visual elements resembles that of the friends page. The main difference is that the photograph plays a more central textual role as the point of departure for the utterances. The diary is the category that was described most of all in terms of its writing, and it is also one of the categories most dominated by writing elements. The same is true for the content page, though it is more heterogeneous. The concepts formulated to describe the content page resembled those of the ego page, but here the informants agreed more on values. They unequivocally stated that text in bulleted lists is perceived as less personal and thus not as good. The textual role of writing The interview data were further analyzed to reveal the informants' general concepts of writing. As the informants name and describe writing in their utterances, they treat it mainly as a visual phenomenon. Generally, they talk about writing as something that does or does not occur. When the informants more specifically describe different types of writing, a general dichotomy between two visual shapes appears. As was already noted, this dichotomy is most relevant in describing the ego page and the content page. It is in fact only when the diary is involved that writing is taken for granted, i.e. what is described on the page is what is written. Based on these observations, the diary seems to be the category most strongly connected to what Kress & van Leeuwen (1996) call old visual literacy. The results of the semiotic text analysis reveal two main principles for making text within the page: the genuinely multimodal one and the mainly linguistic one. According to the multimodal principle, textual units on different levels are created via elements of writing and visual representations or photographs together. The modalities involved are given special functions, which seem to be established according to each page category and thereby related to the function of the page. On one friends page analyzed (see Figure 1), the non-linguistic visual resource plays the role of a thematic anchor, while language carries the personal comment. All the groupings on this page share the same structure. Multimodal cohesion turns out to be not mainly sequential, but rather grounded in simultaneous display (c.f. Kress, 1998). Being aware of the meaning of spatial organization is thus crucial for understanding textuality.

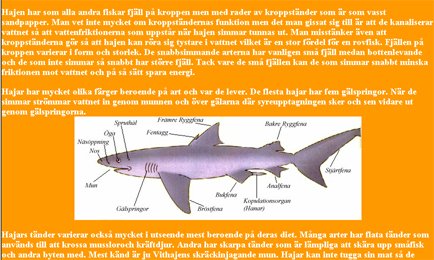

Figure 2. Writing and visual representation on a content page The organization of one content page studied (see Figure 2) follows a different principle. Here, each block of writing constitutes a textual unit, and subheadings help to structure the text hierarchically. Each textual unit deals with one aspect of scientifically-based knowledge about sharks (the subject of this particular page). The blocks of writing are placed one under another and they are broad enough to fill up the width of the page. There is no visual connection between the pictures and any particular block of writing. The relationship between the elements on this content page is not to be found on textual levels such as the transitivity unit or the textual unit , but rather on a more general level. The unity and heterogeneity of the homepage To sum up, the personal homepage can be described as a format that consists of, and thereby both defines and is defined by, a certain number of page categories. An overview of the homepages in the main material shows that the category with the largest number of pages is the content page. However, the index page is the category represented in most homepages, followed by the links page, the ego page and the guestbook. A core of frequently occurring pages can be distinguished, such as index page, ego page, link page, friends page and guestbook, all of which are strongly connected to the social activity of chatting. Other categories, such as content page and the diary in particular, are related to other contexts and even other non-Internet genres. The whole of a homepage is thus dynamic and under constant change, depending on what pages are tied to the overall format. It can be concluded that the personal homepage is heterogeneous in terms of literacy. The parts of homepage use mainly connected to local and relatively private functions seem to belong to a text culture that we have not seen in the public sphere before. Perhaps its roots can be traced to everyday genres such as the party invitation card, the photo album or the scrap book. Within the same homepage, though, we find pages that relate to a more traditional public discourse, and we also find more traditional conceptions of writing connected to these pages. This shows, among other things, that literacy is not single and autonomous - not even in one individual. The future of the kind of homepage studied here is of course unclear. From the observations I made following the study described here, I venture to speculate about two possible developmental paths. The first implies that homepage owners tend to remove large parts of their homepages and only develop certain parts: mainly the diary and the ego page. Diaries and ego pages are also institutionalized by the many writers' communities that have begun to flourish on the web, which act more or less as commercial publishers. Within these communities the writer has little opportunity to create meaning through resources other than language, as the visual appearance is largely standardized. The second path of development is illustrated by a smaller group of homepage owners who choose to develop the visual aspect of their pages, searching for an identity as web designers or graphics artists. Thus the hypothesis of the Internet reversing the semiotic landscape, and the roles traditionally connected to it, remains to be confirmed. Discussion

Homepage literacy and the contextual parameters Let us now return to the parameters discussed above: the parameters of material conditions, domain, power (or ideology) and semiotic mode. Homepage literacy, as it appeared in the investigation reported on, can then be further defined and discussed.

What is significant for the material conditions that personal homepages work under is the split between the material principles of storing the data on one hand and the material principles of displaying them on the other. Storage principles are very different from those in the old paper culture. Even the producer who uses a help program needs to know something about how different documents interact and how they should be placed in the web catalogue to work properly. The principles of display are something different, and it might be said that they can be more or less loyal to the storage principles, i.e. you can choose to create a surface that reflects - and emphasizes - the underlying technical structure, or pretend it does not exist. The web is in itself an interface that suppresses the underlying technical structure to a much greater extent than other Internet systems (such as Gopher or FTP). In fact, the most salient feature that directly relates to actual technical structure is the hyperlink. In my homepage material, most hyperlinks operate on what I call the level of the format, i.e. they are links between texts (pages) and not within texts. If text internal links appear, they are normally dead ends. For example, in diaries you can find personal names linked to little pop-up texts which explain who the people are. After reading this, you close the window and return to the main text. The linking conventions of these homepage owners could actually be seen as part of the same tradition as many paper products. We seem to have certain established ways of binding together texts of different kinds into an overall format, and we have a tendency to interpret material entities (such as the page or the book) as textual entities. Therefore "format linking" is used more than text internal linking in these personal homepages. Thus, the technology can not be said to be a determining factor, but one that is used to re-shape conventionalized ways of making texts. In connection with the parameter of domain, it is debatable whether making and maintaining a personal homepage should be considered as a new kind of private, everyday writing among ordinary people, or rather as the creation of a new public mass media product (with the only difference being that the producer is not professional). The answer suggested by my homepage study is that the kind of personal homepage I have studied is more public than private, which is something every homepage owner is aware of. However, much homepage use is local rather than global, i.e. important parts of the homepage have a limited number of visitors and are thus used within a rather well-defined community. Yet other parts can be written for a rather wide audience and still function within the more local context (and part of its function is that it stretches beyond this context). In many ways a homepage owner takes on the role and borrows the voice of a professional producer. At the same time he or she is very much aware that this is not the case. You could expect that a blurring of domains and traditional roles also would loosen up the constructions of power and the ideological conceptions of literacy on the web. The homepage owners and diary writers in my study have made their products without professional supervision and put them on the web without having to pass any test or reviewing procedure. They are very much their own readers, since they take part on equal terms in a community of homepage owners of the same kind as themselves. And in many respects they tend to see their peers, as well as themselves, as their main critics. But when diary writers talk about writing, very traditional conceptions about literary quality and originality come up. Conceptions of writing are also present when the informants talk about page categories such as the ego page and the friends page. The difference is that here they do not talk so much about the content of what is written, but mainly about the visual surface (and the style a particular shape gives to the whole page). Different page categories, and thus different aspects of the homepage, are connected to different conceptions of writing: some parts to more dominant conceptions, others to what seem to be new perspectives. The possible paths for development of the personal homepage sketched earlier in this paper also fit rather well into the traditional ideological framework which defines writing. If it is true that many homepage owners leave behind their own product to enter a publishing-house-like writers' community, where you actually can be thrown out if you don't stick to the rules, then it shows that traditional constructions of power in literacy find their way into the web - and are welcomed. The fact that homepage owners seem to emphasize the screen as their main material base means that they have chosen the surface as their room for meaning-making. This includes a range of possibilities such as choosing different background patterns (or background colors), shaping the writing in different ways and using other kind of visual expression. It also includes the spatial use of the surface for making meaning. Certain instances of visual, non-linguistic meaning-making that take place on the homepages seem to be a direct result of the wide range of choices and the large array of images offered to the producer. One example is the use of images for seemingly decorative purposes, as when a line of roses separates one part of the page from another, or when a little ladybug is the element that ends the page. These visual representations are used in a non-representative way; rather they work as attitude makers. What seems to be general and more persistent is the way my informants use - and talk about - spatial organization to make meaning on the macro-level. Throughout the material, and in the interviews, page content is displayed and talked about in terms of two different structures: First, there is one part of the page that relates to the overall format, where you find the menu, copyright notes, dates and e-mail addresses. This kind of information is normally found on the left and in the bottom. Then there is the main content of the page.

The future development of the personal homepage anticipated above forecasts a victory of the written word over other semiotic systems of expression. In my text material, the old and the new visual literacy (Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996) seem to govern in different page categories. The more local the page (such as the friends page), the more multimodal it is, as it seems. And these kinds of pages are actually the ones that are most vulnerable to social change. When this particular group of people cease e-chatting with each other, this kind of page become obsolete, while the diary and many content pages find new and less local contexts.

Web literacy? Is homepage literacy, or literacies, then typical for the web? Empirical studies, such as the homepage study reported on here, show the importance of sorting out the contextual factors and finding the ones that are the most interesting in explaining the specific feature in focus. In the case of personal homepages in this particular community, the role of writing can be explained mainly by the social practices connected to different parts of the pages, and by the different writing cultures connected to these practices. The material conditions are seen to serve these cultures, as do the semiotic resources. Also connected to the different writing cultures are the ideological constructs of writing which were expressed by the informants in the various interviews. This generates a methodological challenge for further research into non-dominant literacies: all writing cultures, all literacies, might not have the same need for a metalanguage to talk about writing specifically, or even for talking about text. To reach what is often referred to as ecological validity (e.g. Barton, 1994), we need to find the text concepts and meaning-making structures that are relevant to the users in the specific community, not to the user as a detached individual. The blurring of domains - public-private, local-global and professional producer-everyday consumer - stands out as one of the more generally valid properties of any phenomenon we would want to label web literacy. In fact, I think that this might also be one of the main causes of the increasing interest in Internet-related reading and writing among scholars. The writing practices of new, non-professional writers suddenly become available and visible and then appear as a new, rather exotic contribution to public-sphere discourse. To reduce it to "web literacy" or "web language" would most certainly be a mistake.

Anna-Malin Karlsson, PhD, is a Senior Lecturer and Researcher at the Department Scandinavian Languages at Stockholm University, Sweden. She wrote her doctoral dissertation about personal homepages and is currently studying literacy events and practices in common, non-academic occupations. Homepage:

http://www.nordiska.su.se/personal/karlsson- a-m/eng |

References

|